There’s been a fair amount of talk lately about proactively regulating — and maybe even breaking up — the “Big Tech” companies.

Full disclosure: this post discusses regulating large tech companies. I own shares in several of these both directly (in the case of Facebook and Microsoft) and indirectly (through ETFs that own stakes in large companies)

Like many, I have become increasingly uneasy over the fact that a small handful of companies, with few credible competitors, have amassed so much power over our personal data and what information we see. As a startup investor and former product executive at a social media startup, I can especially sympathize with concerns that these large tech companies have created an unfair playing field for smaller companies.

At the same time, though, I’m mindful of all the benefits that the tech industry — including the “tech giants” — have brought: amazing products and services, broader and cheaper access to markets and information, and a tremendous wave of job and wealth creation vital to may local economies. For that reason, despite my concerns of “big tech”‘s growing power, I am wary of reaching for “quick fixes” that might change that.

As a result, I’ve been disappointed that much of the discussion has centered on knee-jerk proposals like imposing blanket stringent privacy regulations and forcefully breaking up large tech companies. These are policies which I fear are not only self-defeating but will potentially put into jeopardy the benefits of having a flourishing tech industry.

The Challenges with Regulating Tech

Technology is hard to regulate. The ability of software developers to collaborate and build on each other’s innovations means the tech industry moves far faster than standard regulatory / legislative cycles. As a result, many of the key laws on the books today that apply to tech date back decades — before Facebook or the iPhone even existed, making it important to remember that even well-intentioned laws and regulations governing tech can cement in place rules which don’t keep up when the companies and the social & technological forces involved change.

Another factor which complicates tech policy is that the traditional “big is bad” mentality ignores the benefits to having large platforms. While Amazon’s growth has hurt many brick & mortar retailers and eCommerce competitors, its extensive reach and infrastructure enabled businesses like Anker and Instant Pot to get to market in a way which would’ve been virtually impossible before. While the dominance of Google’s Android platform in smartphones raised concerns from European regulators, its hard to argue that the companies which built millions of mobile apps and tens of thousands of different types of devices running on Android would have found it much more difficult to build their businesses without such a unified software platform. Policy aimed at “Big Tech” should be wary of dismantling the platforms that so many current and future businesses rely on.

Its also important to remember that poorly crafted regulation in tech can be self-defeating. The most effective way to deal with the excesses of “Big Tech”, historically, has been creating opportunities for new market entrants. After all, many tech companies previously thought to be dominant (like Nokia, IBM, and Microsoft) lost their positions, not because of regulation or antitrust, but because new technology paradigms (i.e. smartphones, cloud), business models (i.e. subscription software, ad-sponsored), and market entrants (i.e. Google, Amazon) had the opportunity to flourish. Because rules (i.e. Article 13/GDPR) aimed at big tech companies generally fall hardest on small companies (who are least able to afford the infrastructure / people to manage it), its important to keep in mind how solutions for “Big Tech” problems affect smaller companies and new concepts as well.

Framework for Regulating “Big Tech”

To be 100% clear, I’m not saying that the tech industry and big platforms should be given a pass on rules and regulation. If anything, I believe that laws and regulation play a vital role in creating flourishing markets.

But, instead of treating “Big Tech” as just a problem to kill, I think we’d be better served by laws / regulations that recognize the limits of regulation on tech and, instead, focus on making sure emerging companies / technologies can compete with the tech giants on a level playing field. To that end, I hope to see more ideas that embrace the following four pillars:

I. Tiering regulation based on size of the company

Regulations on tech companies should be tiered based on size with the most stringent rules falling on the largest companies. Size should include traditional metrics like revenue but also, in this age of marketplace platforms and freemium/ad-sponsored business models, account for the number of users (i.e. Monthly Active Users) and third party partners.

In this way, the companies with the greatest potential for harm and the greatest ability to bear the costs face the brunt of regulation, leaving smaller companies & startups with greater flexibility to innovate and iterate.

II. Championing data portability

One of the reasons it’s so difficult for competitors to challenge the tech giants is the user lock-in that comes from their massive data advantage. After all, how does a rival social network compete when a user’s photos and contacts are locked away inside Facebook?

While Facebook (and, to their credit, some of the other tech giants) does offer ways to export user data and to delete user data from their systems, these tend to be unwieldy, manual processes that make it difficult for a user to bring their data to a competing service. Requiring the largest tech platforms to make this functionality easier to use (i.e., letting others import your contact list and photos with the ease in which you can login to many apps today using Facebook) would give users the ability to hold tech companies accountable for bad behavior or not innovating (by being able to walk away) and fosters competition by letting new companies compete not on data lock-in but on features and business model.

III. Preventing platforms from playing unfairly

3rd party platform participants (i.e., websites listed on Google, Android/iOS apps like Spotify, sellers on Amazon) are understandably nervous when the platform owners compete with their own offerings (i.e., Google Places, Apple Music, Amazon first party sales). As a result, some have even called for banning platform owners from offering their own products and services.

I believe that is an overreaction. Platform owners offering attractive products and services (i.e., Google offering turn-by-turn navigation on Android phones) can be a great thing for users (after all, most prominent platforms started by providing compelling first-party offerings) and for 3rd party participants if these offerings improve the attractiveness of the platform overall.

What is hard to justify is when platform owners stack the deck in their favor using anti-competitive moves such as banning or reducing the visibility of competitors, crippling third party offerings, making excessive demands on 3rd parties, etc. Its these sorts of actions by the largest tech platforms that pose a risk to consumer choice and competition and should face regulatory scrutiny. Not just the fact that a large platform exists or that the platform owner chooses to participate in it.

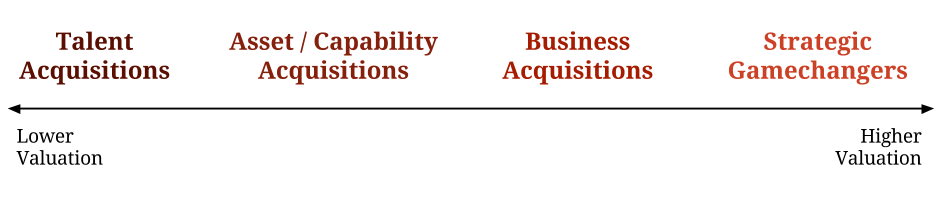

IV. Modernizing how anti-trust thinks about defensive acquisitions

The rise of the tech giants has led to many calls to unwind some of the pivotal mergers and acquisitions in the space. As much as I believe that anti-trust regulators made the wrong calls on some of these transactions, I am not convinced, beyond just wanting to punish “Big Tech” for being big, that the Pandora’s Box of legal and financial issues (for the participants, employees, users, and for the tech industry more broadly) that would be opened would be worthwhile relative to pursuing other paths to regulate bad behavior directly.

That being said, its become clear that anti-trust needs to move beyond narrow revenue share and pricing-based definitions of anti-competitiveness (which do not always apply to freemium/ad-sponsored business models). Anti-trust prosecutors and regulators need to become much more thoughtful and assertive around how some acquisitions are done simply to avoid competition (i.e., Google’s acquisition of Waze and Facebook’s acquisition of WhatsApp are two examples of landmark acquisitions which probably should have been evaluated more closely).

Wrap-Up

This is hardly a complete set of rules and policies needed to approach growing concerns about “Big Tech”. Even within this framework, there are many details (i.e., who the specific regulators are, what specific auditing powers they have, the details of their mandate, the specific thresholds and number of tiers to be set, whether pre-installing an app counts as unfair, etc.) that need to be defined which could make or break the effort. But, I believe this is a good set of principles that balances both the need to foster a tech industry that will continue to grow and drive innovation as well as the need to respond to growing concerns about “Big Tech”.

Special thanks to Derek Yang and Anthony Phan for reading earlier versions and giving me helpful feedback!